On Monks, Girth, and Fine Ale

A front-page news release last week informed the world of the powerful and devastating news that medieval monks were, well, not particularly slim. A front-page news release last week informed the world of the powerful and devastating news that medieval monks were, well, not particularly slim.

Philippa Patrick, from the Institute of Archaeology, at University College, in London said that an analysis of the skeletons of 300 sets of bones found at Tower Hill, Bermondsey, and Merton abbeys showed a great deal of evidence pointing to obesity, including diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis and arthritis in knees, hips and fingertips.

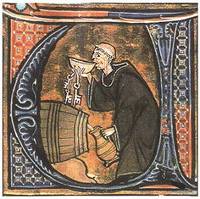

Ms Patrick said: "They were taking in about 6,000 calories a day. Their meals were full of saturated fats." Now, how do you fit 6,000 calories into a diet associated with the ascetic life of self-denial? Only one way. Ale, and lots of it. In the Medieval world, ale (along with wine, beer, mead, cider, and spirits) was the modern equivalent of bottled water. And there's a purely pragmatic dimension to this: ale was the only drink which could be guaranteed not to kill you (unlike water, which, being unsanitary, often would), its consumption was seen as healthy and conducive to strength and vigor, and was often associated with medicinal value (more info here). As to how much was actually consumed, the most accurate records we have come from monasteries, and these indicate a general allowance of between one and two gallons of ale per day. Hence, the weight problem.

But for monastics, there is, paradoxically, an ascetic value associated with ale. Medieval monks were known for their fasting, i.e. abstention from solid foods, which often lasted up to a month in duration. Given that water was unsanitary, and some form of liquid sustenance was necessary for continued health, the monasteries of Western Europe became responsible for some of the greatest developments in modern brewing (the practice of brewing with hops, e.g., began in these monasteries) (see history of beer here).

Yet monasteries were by no means indulgent or libertine in their consumption. Although ale and wine were necessities of life, and could not, for practical purposes, be avoided, care was taken to avoid drunkenness. Note, e.g., the Rule of St. Benedict:

"Nevertheless, keeping in view the needs of the weak, we believe that a hemina [10 oz.] of wine a day is sufficient for each . . . The superior shall use her judgment in the matter, taking care always that there be no occasion for surfeit or drunkenness. We read it is true, that wine is by no means a drink for monastics; but since the monastics of our day cannot be persuaded of this let us at least agree to drink sparingly and not to satiety, because 'wine makes even the wise fall away'" (Eccles. 19:2).

This also took place in the context of a generally ascetic diet and lifestyle. Monks ate two meals a day, often in silence, and meat and fish were generally avoided (more). Many monks, especially the Benedictines, also had rules which obliged lengthy periods of hard manual labor, including corporal works of mercy towards the poor and infirm. This also took place in the context of a generally ascetic diet and lifestyle. Monks ate two meals a day, often in silence, and meat and fish were generally avoided (more). Many monks, especially the Benedictines, also had rules which obliged lengthy periods of hard manual labor, including corporal works of mercy towards the poor and infirm.

Also of note: St. Augustine of Hippo, most likely due to the oft-exaggerated excesses of his youth, has come down to us as the patron saint of brewers.

# posted by Jamie : 8:32 AM

|

|