|

Wednesday, August 11, 2004

|

"Gird up your loins"

"Gird your loins and light your lamps and be like servants who await their master's return from a wedding, ready to open immediately when he comes and knocks" (v. 35-36).

The phrase 'gird up your loins' strikes us as oddly antiquated, even quaint. The sense of the phrase, of course, is quite evident; perhaps 'fasten your belt' 'button up your khaki pants' might be better modern analogies. But this is not an isolated phrase in Scripture; symbolism of 'girding loins' is a common motif running throughout the biblical canon.

The term 'loins' refers to the area running from the small of the back around to the abdomen, spanning the hips, and including the genital area. Hence, the term 'loins' is used as a symbol for human strength and authority (Deut. 33:11, Job 40:16), or fertility (Gen. 35:11,I Kings 8:19). Beginning in the Old Testament, 'girding up one's loins' (i.e., fastening a loincloth) becomes a symbol for preparing oneself for action, readying oneself for obedience to God's will (e.g., God's words to Job, "Gird up your loins like a man; for I will demand of you, and answer thou me," Job 38:3, 40:7). In the New Testament, this is taken in a more moral, spiritual sense. We are told to 'gird our loins with truth' (Eph. 6:13-18), and 'gird up the loins of our mind' (I Pet. 1:6-13). On a more eschatological note, the girding of one's loins can be a symbol of expectation for Christ's return (because one normally 'girds one's loins' only when one is preparing to travel somewhere, it lends itself to the theme of preparation). Thus, the Church of Laodicea is told that, although they think their loins are girt, they are not as ready as they think for the return of the Lord (Rev. 3:14-22). In our passage this Sunday, the same signification is utilized, this time as wedding guests awaiting the Bridegroom's arrival (Luke 12: 31-48).

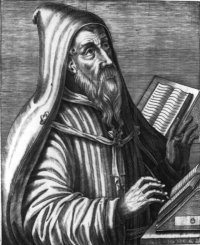

For St. Augustine, the 'girding of the loins' becomes a special symbol of chastity (in that the loins cover the genitals): the 'girding of the loins,' he says, 'is virginity' ( Homily 43, 3). But he also sees this symbolism in terms of a general 'abstinence from unlawful desires' ( Homily 58, 1), of which chastity is only a preeminent example. It can even mean 'departing from evil' in general (43, 2). The themes of moral regeneration and eschatological preparation are, of course, tightly linked for St. Augustine. The Gospel here, he says, bids "us to be unencumbered and prepared to await the end" (43, 1). For the moral framework of our lives must be framed by the hope for eternal life. To fail to 'gird our loins,' to fail to place our hope exclusively in the next life, to love this world instead, is to plunge into the depths of moral absurdity:

"This [present life] at the most is but brief, and of short duration; and yet how eagerly is it sought by men, with how great diligence, with how great toil, with how great carefulness, with how great watchfulness, with how great labour do men seek to live here for a long time, and to grow old. And yet this very living long, what is it but running to the end? Thou hadst yesterday, and thou dost wish also to have to-morrow. But when this day and to-morrow are passed, thou hast them not. Therefore thou dost wish for the day to break, that may draw near to thee whither thou hast no wish to come. Thou makest some annual festival with thy friends, and hearest it there said to thee by thy well-wishers, 'Mayest thou live many years,' thou dost wish that what they have said, may come to pass. What? Dost thou wish that years and years may come, and the end of these years [i.e., Judgment] come not? Thy wishes are contrary to one another; thou dost wish to walk on, and dost not wish to reach the end" (43, 3).

# posted by Jamie : 3:56 PM

|

|